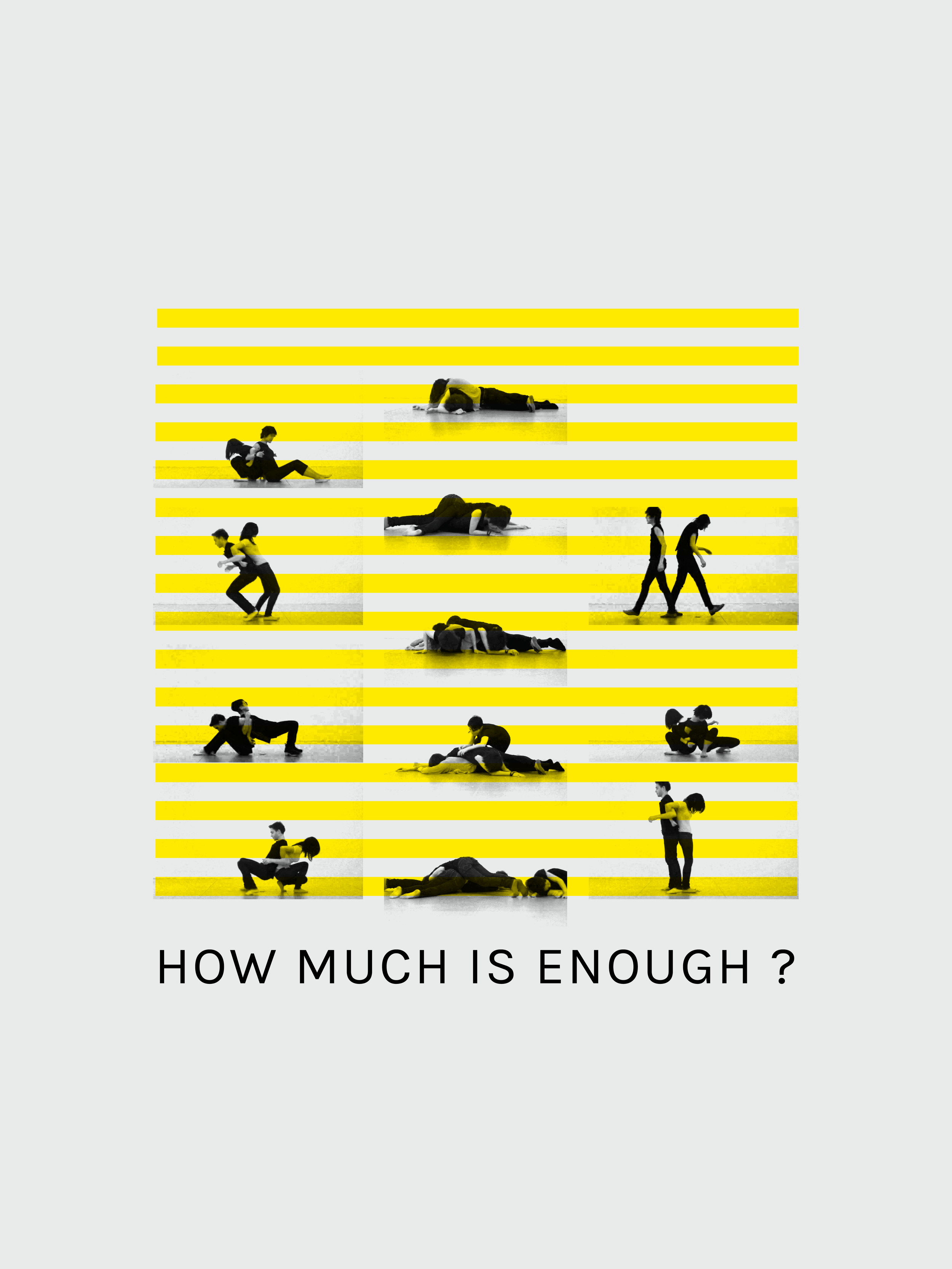

Acting the Words is Enacting the World

In collaboration with Hồng-Ân Trương and the Acting the Words is Enacting the World Collective (Robert Cipriano, Christopher Ferrieiras, Matthew Kim-Cook, Cindy Liang, Israel Giovanni Martinez, Andrew Persoff, Camilla Yvonne Romano and Evalise Salas)

Workshop, performance, installation with videos, screen-printed posters, recorded sound interviews, and zine

2011 – 2013

What are the possibilities for us to make a meaningful living wage for ourselves? Is it possible to engage in an art project that transmits and reveals the relations produced in the process of making? This collaborative art workshop aims to explore the possibilities through an experiment in actions and words.

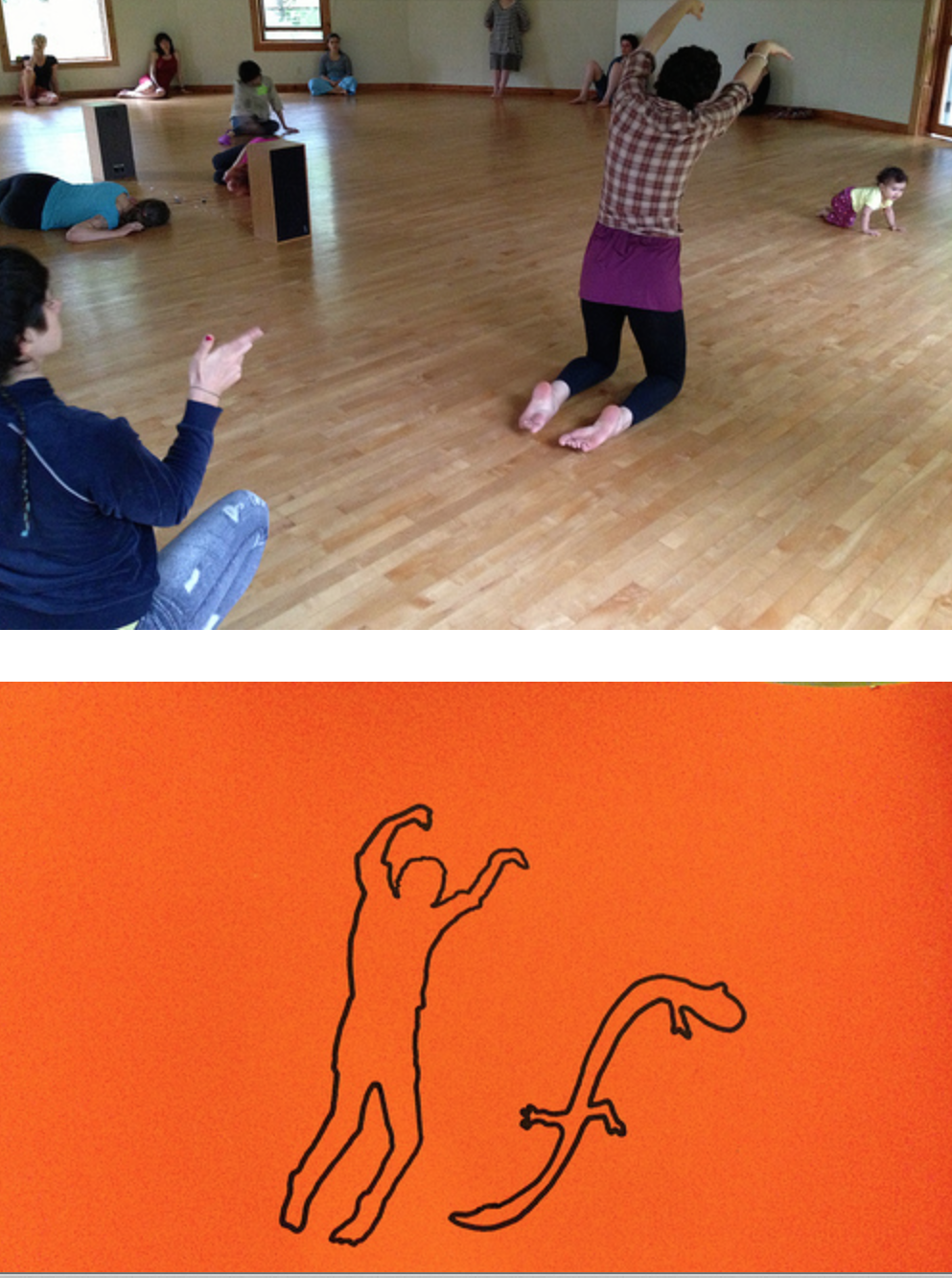

We began with Theater of the Oppressed strategies, collected and formalized by Augusto Bóal, and then further developed them with our participant collaborators, students (age 18-25), to explore poetic gestures that express nuanced dissent against economic structures that over-determine our daily interactions with one another. These students were from various socio-economic backgrounds and lived across four boroughs in NY. In our two-week collaboration, we conducted daily workshops to raise a series of concrete questions about the economy and encourage the students to articulate their lived realities within capitalism. The resulting installation and performances explored the possibilities of what could be by enacting potential, imagined realities.

Fantastic Futures

Online sound archive, performance & workshop series, reading group

fantasticfutures.fm

2010 – 2013

Fantastic Futures is a direct result of my interest in intersecting a professional teaching practice with an engagement in processes of radical pedagogy. The collective began as a team of students, artists, doctors, and future leaders from Iraq and the United States. As the project developed, the core members (Or Zubalsky, Sable Smith, Phuong Nguyen, Solgil Oh, Julio Hernandez) were my former students, with whom I would not have been able to have a sustained pedagogical relationship were it not for this collective because of the structuring of adjunct labor. Over the period of four years (for some of them their entire undergraduate career), we solidified our own processes of collaborating and accomplished a rich repertoire of performance, sound, and pedagogical practices based around themes of technology and social justice.

In 2011, we were awarded a Rhizome Commission for new work, for which we created a free and open online sound archive that examines concepts of the theme of listening and indeterminacy through the recording, collaging, and sharing of sounds between these two countries. The core collective then used this online platform and processes from our collaboration as the base for our performance at the New Museum, workshops and a reading group that we developed with the scientist Jason Munshi-South as iLAND residents in Queens Flushing Meadows Corona Park (2013), and the foundation for a newspaper theater workshop at Yerba Buena Center for the Arts (2013).

Secret School

2009

Secret School is a curatorial platform for experimental pedagogy and collaboration. Previous Secret School Sessions include:

Memory: An installation of the three-channel video installation Wheel In The Sky, by Hồng-Ân Trương.

Statelessness: A conversation with Lin + Lam on their recent work and research on refugees and sovereignty.

Gold: An interactive model economy developed, run, and transformed by economists Daniel Martin, Chris Tonetti, Jesse Perla, and Fernando Leibovici.

Food: A film screening curated by Alexander Stewart, barter platform, and series of zine-making workshops.

Grow: A year of workshops, tours, and street installations around the theme of urban greening and commoning with Colin McMullan.

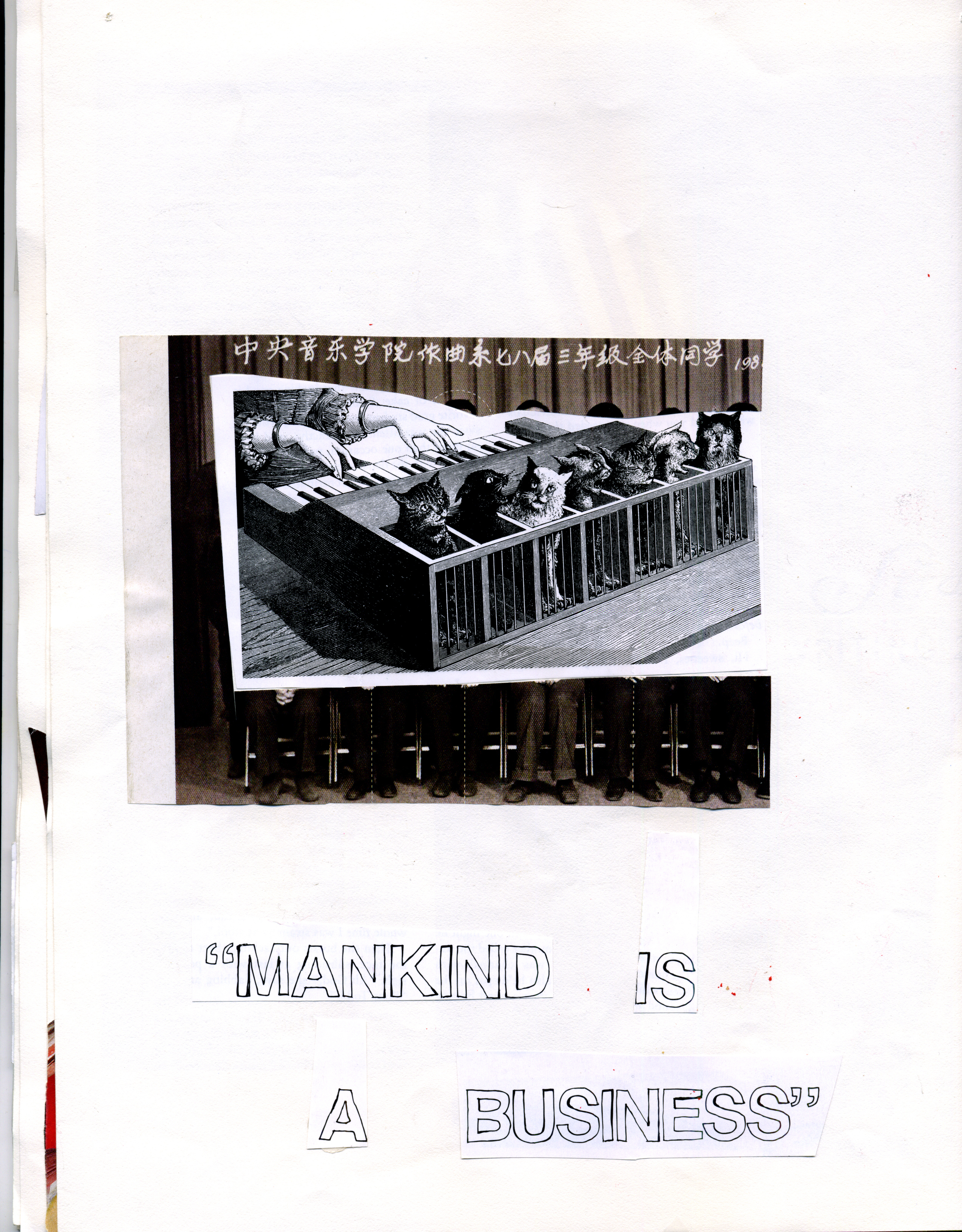

An account of Secret School Session 3: Gold

Daniel Martin (NYU Economics PhD candidate) and I organized a Secret School session in which we created a small labor-based economy and let it run for a few hours to see what would happen. We were curious about the behavior of these temporary markets and wanted to know if they would suffer from some of the same issues as markets in the real world (emergence of black markets, corruption, arbitrage, flooding of markets) or the same kind of abstractions (hedge funds, fiat currency, deregulated financiers), or perhaps alternatives to the model would occur (barter, gift economies).

First, we created all of the elements necessary for the economy to run on its own: consumption goods, a production process, and currency. For goods, we stocked the bar full of beer and cookies that people could only get if they earned money. For our currency, we made hundreds of bags of dirt, each one of which potentially held a gold Obama coin. For production, we established a model factory where people traded their drawings and shapes cut out of cardboard for bags of dirt. Once someone earned a bag of dirt, they could use it to buy goods, go to the central bank and sift out the dirt in the hopes of finding an Obama coin, or keep the dirt as… dirt.

By the end of the night, we were out of raw materials to make into sale-able objects, all of the dirt had been sifted out, our central banker (Fernando Leibovici) had quit, the empty bags of dirt had been turned into a fiat currency (backed by nothing), our factory boss had changed the wage system, catalyzing a group of computer scientists to create a system of arbitrage by stockpiling beers and bribing new-comers to the economy, some Haitians kept threatening all participants in the economy, everything went to hell, but the prices of cookies and beer (adjusted by Chris Tonetti, shop boss) ended at an equilibrium.

I asked Jesse Perla, factory boss, to reflect on what happened:

“Equilibrium”

1. What did you expect to happen? I thought things would start off fairly stable as the economists and others figured out how the system worked, then everything would fall apart. I thought there likely would be some fundamental flaw in how things were setup that people would exploit causing great insanity. I thought that the other possibility was that things would be fairly boring: people would do a little work to get a beer at a normal frequency and that is about it.

2. What were you wondering might happen? I wondered if it was possible to reach some kind of an “equilibrium” fairly quickly. Part of this question is based around the quantity of alcohol that people wanted to consume (see later). The question in my mind was if the system would be relatively stable, and no one would disturb shit on their own, and that I would have to introduce some insanity to see how things happened. This is an interesting question in economics: Whether these kinds of systems are inherently stable on their own and how they respond to external nuttiness.

3. What happened? The system worked out fairly well. Things were fairly stable as there was a ramp-up in drinking, people arrived, and the money was circulated. I am not sure if things would have remained stable without my intervention, but everything seemed fairly smooth until I started messing with wages. Then all hell broke loose, but amazingly the prices of beer and cookies correctly responded to the changes in wages fairly quickly and things reached a new equilibrium rapidly.

4. What surprised you? That things worked for 3 hours. I was pretty sure everything would fall apart.

"Do People Understand and Correctly React to Prices?"

1. What were you wondering might happen? I thought that people would be a little confused at first, but fairly quickly everyone would understand the wage and beer prices and track them.

2. What were you wondering might happen? I was wondering if there would be an effect that people would work harder as wages increased. Even if the prices raised proportionally.

3. What happened? It seemed that people responded to higher wages at first, but that people adjusted to the new price level quickly. Most people “got” the different wages and prices fairly quickly, though many didn’t keep track of the changing wages while they were doing work. Eventually, people would track the wage changes as they worked.

4. What surprised you? The Haitians. I thought that everyone would get the idea of prices, but they didn’t. It was a completely different world-view where everyone here who grew up in a liberal democracy got it, but they were completely confused and frequently infuriated as prices changed.

“Would Non-Official Markets and Trading Spontaneously Pop Up?”

1. What were you wondering might happen? I was pretty sure that some kinds of spontaneous trading would occur, but wasn’t sure what or how. I also thought that somehow they would find a way to bring down the system.

2. What were you wondering might happen? If the possibility of arbitrage would spur spontaneous trading or if it would happen due to the impatience of drinkers. I was also interested in whether a single person of group would end up as a “bank” lending out beers and buying work independently of me as the factory owner.

3. What happened? I am not entirely sure, but it seemed that there were a lot of trading going on. A group of CS guys seemed to be in the middle watching prices and looking for arbitrage opportunities. I also tried to spur some other markets by adding a beer as part of the “work” necessary to get a wage. My idea was to see if people would adapt to this and how long it would take. It wasn’t very long, and I believe that some people were making a killing selling beer for work.

4. What surprised you? The level of stealing in the economy.

“Level of Alcohol Consumption and Quality of Work”

1. What were you wondering might happen? Thought that people would get a little lazy as time went on.

2. What were you wondering might happen? Wasn’t sure if people would drink a lot more than normal or if the fact that they had to work for beer would cut down on consumption.

3. What happened? People got wasted. They seemed to enjoy doing the work.

There were some people who were just doing the minimum possible to get a sequence of beers, but they were the minority.

4. What surprised you? The level of drunken troublemaking was very high. And the quality of work was also very high.

“Economists vs. Others”

1. What were you wondering might happen? Thought that the economists might understand the arbitrage opportunities more than others.

2. What were you wondering might happen? Was wondering whether the artsy types would get fleeced by scheming mathies.

3. What happened? The CS guys were the hedge funds and the economists became criminals stealing beer.

4. What surprised you? That people would bother to sit in the middle, watch prices, and try to make major profits.

I also asked Francis Hwang, one of the “CS guys” to comment:

1. What were your first reactions to the scene? First reactions were that it was fun. We got there fairly early and we had a chance to accumulate assets before other people got there which ended up being really advantageous.

2. Did it feel like a real economy? Yeah, in a few ways. I liked the way that you could make various tradeoffs depending on what you wanted vs what others wanted. For one thing, I don’t drink shitty beer, so I kept on trying to trade up to nicer beer. Meanwhile my friends Alex and David were fine with shitty beer, and end up stockpiling quite a bit of it actually.

3. How did you react/change the economy? By the middle of the event, Alex & David had a lot of canned beer and, if I remember correctly, there were a lot of things where you had to start out with one can of beer. So basically they would loan out a can of beer to other people to get them started, for some sort of interest.

4. How could we change the model in order to learn more about the way that the economy works/the way that people make decisions? I think the trickiest thing was that there were a handful of people setting prices for things, and then the rest of us were reacting to how those prices moved. It would’ve been cool if prices changed more dynamically in response to other events. For example, if people could set up their own prices for canned beer, and then you could surprise people by releasing another 24-pack of canned beer, flooding the market. etc, etc.

5. How can you see this type of “game” being applied to learn/subvert/steal/etc? I think it was a pretty good intro to trading mechanics–that’s the sort of thing that’s hard to understand until you’ve done it with a lot of different people. As to whether you could use those simulations for other sorts of learning, hard to say.

Finally, I ask Daniel Martin some questions on economic experiments and economics education:

1. Do they run these types of experiments in Economics classes? My impression is that only a small number of instructors use experiments to teach economics, but they have put together some great resources to help others do the same: http://people.virginia.edu/~cah2k/teaching.html (online) and http://www.marietta.edu/~delemeeg/games/ (offline). One of the most memorable classes I have ever taken featured a simple market (of just 8 students), where the “invisible hand” moved the market price to where supply equalled demand.

2. How else do you learn about the economy? We primarily learn and teach by explaining how simple (and not so simple) models of the economy deliver strong predictions about how policy changes will impact the “real” economy.

3. How do these methods of learning about the economy affect policy makers? It leads us to believe that markets function as well as the ones in our models. On the other hand, learning through experiments often illustrates that while economic theory does surprisingly well at predicting behavior in many settings, there are important and systematic deviations from theory that might be explained by emotional factors, misperception, confusion, and unmodelled power dynamics.